Discovering Omi Beef

Contents

- vol.5 Omi Beef. Into the Future

-

vol.4 Rice Farming in Shiga Prefecture, under Japan’s Strictest Environmental Standards.

Tsutomu Takeyama, Takeyama Farm - vol.3 Tradition and Creativity: Shigaraki potter, Katsunori Sawa

- vol.2 Koh Kentetsu talks about Omi Beef - the wagyu the world has been waiting for.

- vol.1 First Impressions – the cattle of the lake

Omi Beef. Into the Future

From Father to Son

Omi Beef. The oldest of the three major wagyu beef brands in Japan, with over 400 years of history, including being enjoyed by the shoguns of ancient Edo in a time when meat was rarely eaten in Japan at all. But what of the future, and the next generation of Omi Beef farmers? To find out, I went to visit Tatsuya Haito at Haito Beef Farm, in Dainaka, just outside Omi Hachiman.

“I’m the third generation. My grandfather kept cattle, then my father expanded the farm, and I have taken over from there.

Originally I had no plans to take over. I was working in a hospital. But I saw a TV show about young fishermen taking over from their fathers, and that made me decide to come back. (laughs)

Omi Beef has such a long history, and I thought that, as the eldest son, if I didn’t carry on here then one more cattle farm would disappear, and the Omi Beef brand would get that bit smaller. So I thought I should come back and have a go at it. I really didn’t think very deeply about it at the time.”

That was eight years ago, and Tatsuya worked for seven years with his father before taking over the farm one year ago. In an age when the number of people continuing family farms is rapidly decreasing, the Dainaka area is a rare exception, where a quarter of the farms have a successor in place to carry on.

“My father’s generation set up a ranchers association back in the day. Now that there are so many successors in place, we have changed the name to ‘UshiLab’ - or ‘cow laboratory’. All the members are from the Dainaka area. There are 12 of us now, the oldest is around 40 years old, but most of us are the same age as me, around 33 or 34.

The price of calves and feed has gone up so much, farmers like me who buy in calves to fatten are headed straight for bankruptcy if we don’t do something - us younger generation are all feeling the dangers.

Right now the definition of Omi beef is simply based on the amount of time the beef is raised here, but I think we really have to move things forward and make a clearer, more concrete definition, that makes the brand stronger in the eyes of the consumer.”

The UshiLab association, which was started in July 2012, is one way to begin that process. The aim of the group is for the members to be able to research and educate themselves about producing tastier beef, and also advertising themselves.

“We haven’t done all that much yet, but we are beginning to research about producing better beef. What kind of feed to use, and the different results that has. For example at the end of last year we worked with Kyoto University on a project to add vitamin C to the feed. We plan to continue with those kind of projects, and keep researching about producing really tasty wagyu beef, instead of wagyu beef that just has a lot of marbling.”

The Hunt for “Delicious”

“Right now my business is buying in calves to fatten for market, but I plan to start breeding myself. To begin with I will have to sell the calves on, but gradually we’ll be able to fatten them right up to market. If I can get good quality seed, then I can do whatever it takes and really start to produce what the beef I want. I want to be able to sell beef that is born and bred here in Shiga. Omi Beef is already known for its clear fat, and the taste is very highly rated, but I think we can take things one stage further still. ”

The members of UshiLab are building on the know-how that has been passed down to them from their fathers about rearing calves, and pushing things further, to breed their own calves and take them right through to a sellable product.

The flat lands of the Omi plains are fed with water from Lake Biwa, the heart of Shiga Prefecture, known as Mother Lake. And it is here, in the low-roofed cow sheds dotted among the rice fields and aired by a constant breeze from the lake, that Omi beef are raised.

On the day I visited Haito Farm, a traditional hoof-trimmer was working his way round the cattle one by one, trimming and cleaning their feet with a specially-designed knife.

“In this area, we use the straw from the local rice fields to feed the cattle. And then the muck from the barns goes onto the paddy fields as manure.”

The young farmers in Dainaka are keeping up the traditional farming ways. The rice farmers and cattle farmers work together, the cow dung feeds the rice, and the rice straw feeds the cows. This simple, traditional rotation of resources is one of the things that maintains trust in the Omi Beef brand.

I asked Tatsuya what is the best thing about being a beef farmer, and his answer was immediate.

“When someone eats the beef I’ve produced, and tells me it tastes great. That’s better than all the awards put together. ”

In that simple truth, no doubt, is the answer to the way forward for the next generation of Omi Beef farmers.

Tradition that Builds a Future

Throughout these articles, I’ve tried to find out what it is that makes Omi Beef so delicious. And the one thing that comes up everywhere I go is the natural environment of Shiga Prefecture. In order to protect the water from Lake Biwa, which is vital to the whole of the Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe area, the environmental standards in Shiga are the strictest in the whole country. Perhaps because of that, not only is the quality of the water par to none, but the farmers and producers we met are all acutely aware of and conscientious about protecting their local environment.

Shiga is the oldest beef-producing and cattle-trading are in Japan, where the techniques for raising delicious beef have been polished over centuries. The water, air, earth, the whole environment… all these things come together to become the pride and care that Omi Beef farmers take in their work.

And nowadays as consumer tastes change, and different kinds of beef are required, so the beef farmers in Shiga have the knowledge and mindset to adjust and improve with the times. Just like the Omi merchants of old, who pushed new innovations while at the same time protecting and maintaining valuable customs, Omi Beef farmers are working into the future, with a healthy mix of enterprise and tradition.

Rice Farming in Shiga Prefecture, under Japan’s Strictest Environmental Standards.

Tsutomu Takeyama, Takeyama Farm

Work with care, and raise the quality of your produce. That way the customers will always come to you, even if your price is high.

One thing that is a given when you visit Omi Beef cattle farms is the calm and friendly disposition of the cows you meet. That must have something to do with the environment in which they are raised. So what is it about Shiga’s environment that makes it so suitable for livestock farming? To find out more, I went to meet Tsutomu Takeyama at Takeyama Farm, in Ryuo-cho.

Takeyama-san grew up on an egg farm run by his father, but it wasn’t till he was 30 that he came back to Ryuo-cho and founded Takeyama Farm. He built a grape plantation on the land his father had used for chickens, and currently rents land nearby where he grows rice, wheat, soybeans and vegetables on a large scale. Besides actually running the farm, Takeyama-san works hard to bring school children, clients and consumers to the farm to see how things are done. The rice fields cover 25 hectares of paddy fields with a variety of different table rices, plus 5 hectares of sake rice, most off which is distributed in the local area.

“I want to farm in a way that my farmhands, and kids and younger people in general say, this is cool,” says Takeyama-san, and the paddy fields and work areas are indeed all immaculate.

“The local Matsuse sake brewery used to use Yamadanishiki rice from Joto, in Hyogo Prefecture. I think they still use some rice from there, but partly because Ryuo-cho started growing “Kankyo Kodawari Mai” rice the quality is actually better than the Yamada rice from Joto, now. Nowadays Matsuse uses a lot of rice from local, Ryuo-cho farms. ”

“Kankyo Kodawari Mai” is rice grown and produced under Shiga’s strict regulations aimed at producing safe and environmentally friendly produce. The Japan Agriculture Green Omi Coop in Ryuo-cho, where Takeyama-san farms, introduced the regulations in 2001, and by 2016 over 2,700 hectares of farmland was covered, with more being added each year.

http://www.jagreenohmi.jas.or.jp/about/toresa05.html

“We always talk with our customers and partners about what kind of rice they want. I encourage them to come to the farm and look round the fields, actually get down and take a sheaf of rice in their hands, and we’ll talk about how this year’s crop is compared with last year’s, and so on. So, you know, I have to be sure that I’m growing rice I can show off to them.”

Takeyama-san’s rice is also grown under the watchful, and strict eyes of his customers.

“I could just cut costs and grow things on a large scale, but I prefer to concentrate on quality and grow the rice my customers want. And the end result is, I actually get a better price for my rice. I think that’s the right way to go about things.

Even with our rice sacks, as a professional I’m always careful that our bags are beautifully folded and packed for the inspections at the Coop. The inspectors can see the care that has gone into our rice just from the sacks, so they often tell me they know the quality the grain will be even before they’ve opened up the bags.

When I was young, we were always told to make sure our work was cared for and beautiful. You’re really busy and it’s hard to keep up, but it shows in your results if you put your heart into your work, always aware of things like keeping the grass cut back tidily, looking after the fields, basically farming with love. I was taught to do that, and I always tell my farmhands too that they should “farm to be seen”.”

Talking with Takeyama-san, I can hear the same pride and care that the Omi Beef farmers show towards their cattle.

The Strictest Environmental Standards in Japan

“You know, if you asked me what is difficult about farming with natural fertilizers and using very low levels of chemicals, there’s really not much to say. We’ve been doing it for over 10 years now, so it’s simply standard practice nowadays.

When the Environmental Standard was introduced by the local government, I think the target was to reach 50% of certified farmland. Right now 65% of the rice-growing area of Ryuo-cho is certified. I think we’re the largest in the local area, and one of the highest in the whole prefecture, too. Here in Shiga that is just becoming the norm, and a lot of people are farming at even stricter levels. Japan as a whole hasn’t caught up that far yet.

Each prefecture has standards and restrictions, but we have Biwa Lake on our doorstep to think about, so Shiga has always been stricter about farm chemicals than other areas. We’re only allowed about half what the other prefectures can use.

And that means we’re all acutely aware of our natural environment, too. Biwa Lake is the water source for the huge urban areas of all of Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe, so I guess it’s instinctive for Shiga farmers to be concerned about the quality of the water. “

Shiga prefecture’s environmental standards are at the cutting edge in Japan, and the farmers too are becoming more and more positive and enthusiastic about maintaining and improving them.

From field to plate: farming for environment and tradition.

“I think the kind of rice people buy depends on the person eating it, their age and lifestyle and all sorts. And different kinds of rice are better for boiling, or for frying, or for other ways of cooking, too.

In general though, families with children will buy the kind of rice the kids like. The kind of rice they get for school lunches. That’s the key. We have just one school lunch catering center here in Ryuo-cho, so it was simple to get things started, and we’re been serving locally grown Koshihikari Kankyo Kodawari Mai rice at all the schools since 2003. The local Board of Education helps out with farm trips, too.

I think it’s really important to be connected with education, and for the children to learn about where their food comes from. ”

Takeyama-san talks a lot about education, but it’s not only about passing things on to the next generation.

“Personally, and this is the company policy too, I want to preserve our traditional landscape. To preserve the landscape, we have to preserve the paddy fields and Japan’s rice culture. Our festivals here in the countryside, they are all deeply connected to the culture of rice and grain production, too.

And to look after the water system and the natural landscape it provides for, you need the paddy fields. It’s the farmer’s job to preserve that. I was once asked by a member of parliament if farming is an industry or a culture. But you know, I don’t think it’s either one or the other. I think you need to think of both together, somewhere in the middle. I think you need to be thinking about cultural heritage, and of course food and healthy eating. I would like to think we farm rice to satisfy both people’s stomachs and their lives as a whole.”

Environmentally friendly farming, especially on a large scale like at Takeyama Farm, is costly and time-consuming. But for Takeyama-san there is no hardship in that, it is simply the basic standard, and he is already moving into farming with no chemicals at all. And it’s clear too that farming for him is not simply about producing delicious food. There is so much more to it than that.

Farming that is in tune with the environment, be it arable or livestock, leads to safe and healthy food on our tables. The strict standards set by Shiga prefecture mean farmers can work to keep the soil rich and water clean, while providing us with delicious food we can be confident in. That is the same spirit that I have seen in the many Omi Beef farmers I’ve met across Shiga prefecture, too.

Tradition and Creativity: Shigaraki potter, Katsunori Sawa

Shigaraki, one of Japan’s six key pottery towns

With 400 years of history, Omi Beef is the oldest beef brand in Japan. And while Shiga can boast of its position as the origin of beef cuisine in Japan, the prefecture has another tradition that has been around even longer, Shigaraki pottery. I went to visit potter Katsunori Sawa to find out more.

“I’m the fourth generation in our family. My father was the first to be an artist potter, but we’ve all been Shigaraki potters. My grandfather didn’t make traditional style ceramics though, he had a company that made braziers, and before that my great grandfather was what was called a “namaya” back in the days when the work was divided up, so he made the clay bases.

I went to college to learn ceramics first, then I apprenticed with Goro Suzuki in Aichi prefecture. I learnt about decorative painting from Goro-san, and nowadays I do that and traditional Shigaraki as well.”

“The main feature of traditional Shigaraki pottery is that they are fired in a wood-burning kiln without using glazes. Nearly all the major pottery areas started in the Momoyama era (late 16th century) making tea-ware. But Shigaraki originally specialized in large urns and bottles for transporting grains and things, and so perhaps using no glaze was better for the grain.

Also, most of the clay in Shigaraki is white, while nearly all the other areas have red clay. So a striking feature is the clay around here doesn’t have much iron in it. The way the color is achieved is through a chemical reaction with the pine ash in the kiln. Where the ash touches the pot in the kiln, it turns red or green, and the other side where no ash touches might stay the color of the clay, quite white. And then if the molten ash is cooled quickly it turns to glass.

You can tell to a certain extent what the finish will be like by where you place the pot in the kiln, but you can’t calculate anything exactly, so no one pot will ever be the same - for better or for worse. The best moment is opening the kiln, wondering whether you’ve got some good pots.”

The fire in the kiln, the covering of the ash, the cooling…. all can only be controlled up to a point, but after that it’s up to nature to take its course. I am reminded of the Omi Beef farmers, choosing calves with a good bloodline, feed, water, the weather and environment. A mixture of experience, intuition, and the quirks of nature all go into rearing ideal, individual beef animals.

Traditional techniques, original style.

“Whatever area the work comes from, ceramics from the Momoyama era all look quite fresh even now. You never feel the design is old, you know. I think they grow with use over all those years, too. That really makes me want people to use my pots, too.

If you were to re-fire a Momoyama period pot, it would become a completely different thing, even though the shape wouldn’t change. Over the years the crazing and glaze has aged and if you were to re-fire it all the organic stuff would burn away, so it would be completely clean, and change into a quite different thing.“

As Sawa-san talks enthusiastically about his work, surrounded by pots and dishes of all shapes and sizes that overflow out of the workshop door, he pours us freshly brewed coffee into cups he has made himself. Up till then the works had all been silent on the shelves, but as the hot liquid fills the cups it’s as if they begin to breathe and come to life.

“The designers back then were incredible. Think how far apart the pottery towns of Oribe and Karatsu are. Back then they had no internet, very little way of communicating. And yet there are pots where the decorations have exactly the same design. That must have been produced and directed by designers in Kyoto. I think the Momoyama period designs were almost all produced from Kyoto. In those days tea-wares were for the high end of society. Just a handful of people spent a huge amount on these things, and they would have wanted to be sure they had the best. It was more a hobby than a business. “

Wagyu is famous the world over now, but originally in the Meiji period it was the “bakuro” traders in Omi who, just like in the ceramics world, were the “producers” in the beef world, and managed the demands and needs of the beef market across the country.

“There was a time when Shigaraki completely disappeared. The old houses like Raku in Kyoto or Hagi in Yamaguchi are in their 15th generation, so they’ve been going since around the Momoyama era. But even the oldest Shigaraki houses are only 4th generation. In the Edo period Shigaraki was urns and bottles, and then by Meiji they were mass-producing braziers and stuff like that to sell to the general public. It was only after the war that the craft movement was revived and things really got moving again.

Nowadays some people carry on the traditional style, and some are working on completely new, different things, so both live side by side.

I’m more interested in working in my own style than traditional Japanese stuff. I think that’s the era we’re in right now. Respecting traditions, but creating new things for your own time. The techniques might be traditional, but I want to make ceramic that are my original work.”

Japan has more than thirty thousand companies that have been in business over 100 years - by far the most of in any country in the world. Just like in the potteries, keeping things in the family is no different for Omi Beef farmers. And as the times change, so peoples tastes change too. Farmers, too, work to keep traditional techniques alive, while constantly adjusting them to the times.

Koh Kentetsu talks about Omi Beef - the wagyu the world has been waiting for.

I had a chance to sit down with culinary researcher, Koh Kentetsu, at the highly exclusive Omi Beef restaurant, Gion Hosowari, in Ginza, Tokyo. Koh has spent his career traveling Japan, Korea and Asia researching home-cooking across the eastern hemisphere. And for him, despite being the wagyu brand with by far the longest history and tradition in Japan, today Omi Beef is the cutting-edge wagyu the world has been waiting for.

Wagyu, Kangyu and Omi Beef

Tom:As a culinary researcher you are involved in all sorts of activities, but what is the thing that interests you most at the moment?

Koh:It has been much the same from the start - most of my work involves spreading the word about home-cooking. Eating with your family, cooking with your kids… my main work is in bringing people together via food, and cooking.

Tom:Home-cooking. Do you eat mainly Korean food at home?

Koh:As a kid we ate a lot of Korean food, yes. But my mother loved to cook, so she made Japanese food and all sorts. Japanese home-cooking is often cuisine from all around there world, so I learnt about a lot of different types of cuisine.

Tom:What about eating beef at home?

Koh:Korean food uses a lot of beef. It’s not common in Japan, but we make stock from beef. That’s pretty much standard.

Tom:How do you make Korean beef stock?

Koh:It’s mainly made from beef shank. To do it properly you would start by boiling the meat down, and mixing beef stock with konbu stock.

Tom:Beef and Konbu! That’s interesting.

Koh:And you make things like kimchi with it. Beef stock is the base, mainly. In Korean restaurants, the richness of the soups etc, that comes the from beef stock.

Tom:Really? What kind of beef is eaten in Korea?

Koh:Mainly red meat. There’s a Korean brand of beef, called Han-u.

Tom:Han-u?

Koh:Yes - the original Korean beef. Nowadays beef comes in from Australia and other places, but there is a movement to revive the original Han-u beef.

Tom:Does it have a different flavor to other beef?

Koh:Sure. It’s the deliciousness of the red meat that is special. And it’s good for making stock. It’s great made into a soup.

Take the stage, Omi Beef

Tom:Do you remember the first time you had wagyu?

Koh:Wagyu… I’m not sure. We lived in Osaka when I was at primary school, so it was Kobe beef, then.

Tom:Did the marbled fat surprise you?

Koh:The softness is amazing, isn’t it? As a kid at home, on special occasions we would have wagyu, not han-u. Wagyu’s the one for those occasions, you know?

Tom:Do you still use wagyu a lot now?

Koh:As I get older, it gets harder to eat so much if there’s too much marbling. But Omi Beef has a great balance - I think it’s number one among the wagyu brands that way. Kids and older people and a broad range of people can enjoy it.

Tom:What is it that makes Omi Beef special, then?

Koh:Recently there’s been a move towards red meat, for example the red meat in Kumamoto beef is highly prized right now, but when it comes to special occasions, people still want marbled wagyu. Omi Beef has a really good balance between the marbled fat and the red meat. Not just the look of the marbled meat, but a solid taste of red meat, too. The flavor of the red meat really comes through. That’s what makes it so great. I think the thing about Omi Beef is it’s the best of the kind of beef that is popular overseas, and the best of wagyu, brought together.

Tom:Beautifully marbled wagyu, but with a solid beef flavor.

Koh:That’s right. That’s what you really want, isn’t it? Japanese food is hugely popular around he world right now, and there are loads of wagyu fans, too, but when it comes to beef, if there’s too much marbling you don’t feel like you’re eating beef. I’ve always been looking for a wagyu that brings out more of the goodness of the red meat.

Tom:Maybe Omi Beef’s day has come?

Koh:I think so, yes.

Omi Beef, for special occasions

Tom:You have travelled across Asia researching home-cooking. What traditions are there of eating beef at home?

Koh:You know, I spend a lot of time way off in the deep country, and there really isn’t much beef eaten there. Beef is usually reserved for festivals, or New Year, those kind of special occasions.

Tom:Yeah - originally, beef wasn’t an everyday food.

Koh:In that way, although distribution and so on has made beef more available, I think the specialness of wagyu is something we should protect. Something to be eaten on special occasions.

Tom:How about using wagyu in non-Japanese cuisines, like Korean or other cuisines?

Koh:The way wagyu has its marbled fat, I’m not sure how much variation you can get from it. It’s a bit tricky. But the balance of Omi Beef, the way the fat melts in your mouth, but you still have a solid meat taste, too, I think the way you could use it… I mean thinking of about all kinds of cooking styles around the world, of the three main wagyu brands, I think Omi Beef has the most potential.

Tom:There’s a dish called Junjun in Shiga prefecture - the local sukiyaki. A few months ago an Omi Beef farmer treated us to a local junjun feast. The way it is made varies from home to home, but basically it’s simply a big mountain of the green stems of leeks and chinese cabbage put in an iron sukiyaki pan, covered with wagyu to make a kind of lid, and simmered just like that. The only flavoring is a little bit of soy sauce. In the same way you would make a beef stock, the flavor comes from water in the vegetables and juice from the meat. With just a dash of soy sauce. That’s all. And it’s so good! But we tried it at home later with some reasonably good wagyu from the store, and it just didn’t work at all. In the end we tried adding a bit of sugar, and sake and more soy sauce, but… That flavor comes down to top quality Omi Beef.

Koh:It’s all about local people knowing how to get the best taste out of local produce. Bringing out the potential in the ingredients. Omi Beef’s special flavor is kind of like a well kept secret.

Tom:That junjun is exactly what you were saying about home-cooking for special occasions. It’s usually eaten in the winter - the whole family will gather together on a special day and have junjun - or sukiyaki. It’s a special treat.

Koh:Yes - and on those occasions you want to really enjoy a special feast.

The next generation of wagyu - Omi Beef

(The beef arrives)

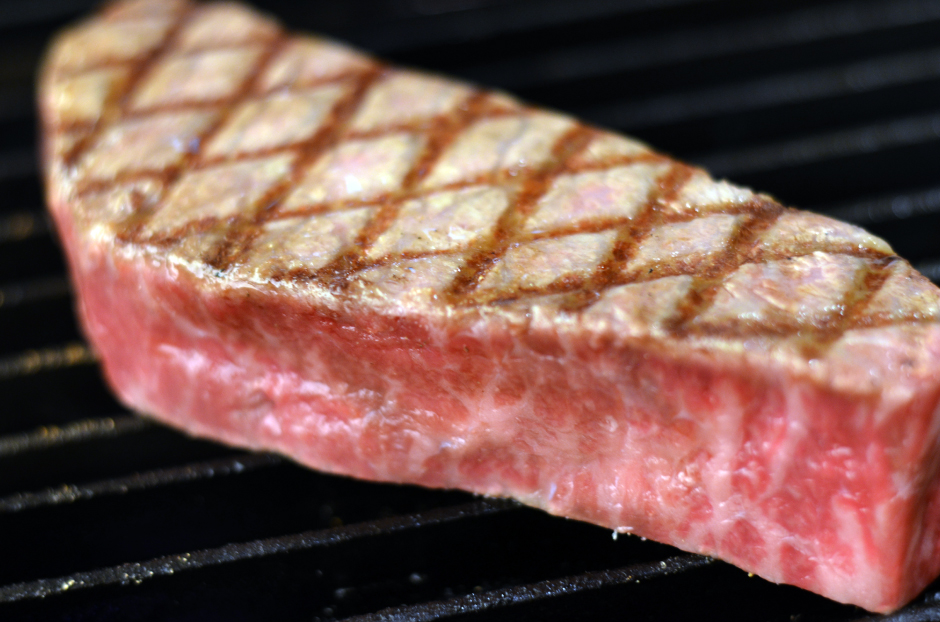

Koh:Wow! That’s amazing - the marbling is beautiful!

Tom:Ahh - that smell! It smells almost nutty.

Koh:(Chef) Yuko Hattori said once, when he took wagyu to an event overseas. There were all kinds of different beef from around the world being cooked barbecue-style, and the aromas were all quite different, but everyone gathered at the wagyu because the smell was so good. It has a unique aroma. The smell alone is almost enough!

(Takes a bite)

Amazing! What is this?! The outside is crunchy, and the flavor inside!

This beef flavor, makes me want to put it in a soup. The umami and juiciness is amazing.

It’s a steak, but the crispy outside, the softness when you take a bite, that juicy, stew-like umami, there’s no other brand of wagyu that will give you that. Omi Beef needs to get out there more! There should be more of this - it’s just too good!

It has a long history, but this is the cutting-edge of wagyu. Omi Beef is exactly the wagyu that everyone is hoping for right now. It has the marbling, and the red meat is delicious, that’s just what everyone wants, isn’t it? Wonderfully flavored red meat, with delicious marbled fat, that’s Omi Beef.

Tom:You can see why the shoguns treasured it as medicine 400 years ago!

Koh:If I could, I’d have this everyday! (laughs)

First Impressions – the cattle of the lake

Tom Vincent

By now we’ve all heard of wagyu - the Japanese beef with its richly marbled steaks, and melt-in-your-mouth texture. If you live outside of Japan, you’ve probably seen it sold as Kobe beef, and most likely your dinner will have been bred in the US, Australia or the UK, from a mix-breed of Japanese and local Angus or other cattle.

But if you know your wagyu, you will know that there are several different brands within Japan, and among them, the three the Japanese prize highest are Kobe, Matsusaka, and Omi. (n.b. it’s pronounced with a long ‘o’, like “Oh me!”. )

Look on the web in English, and you will find plenty about Kobe Beef - the brand is so well known around the world it is almost synonymous with wagyu as a whole - and lots on Matsusaka Beef, too. But there is precious little information in English about the third brand, Omi. And yet, Omi is the oldest wagyu brand by hundreds of years. And, according to many of the top chefs in Japan and increasingly around the world, it’s the tastiest, too.

Omi is the old name for Shiga, the prefecture situated slap bang in the middle of Japan, and enveloping the vast and magnificent Lake Biwa. Abutting Kyoto, the ancient Japanese capital famed worldwide for its temples, maiko girls, and exquisite cuisine, Shiga is where much of the famous Kyoto ingredients come from - so much so that it is known as Kyoto’s Kitchen.

And the secret to the abundance of delicious foods produced in Shiga, is Lake Biwa. Shiga’s vegetables, rice, tea, freshwater fish and shellfish, soy sauce, sake, miso - all owe their existence to the delicious, crystal clear waters of Mother Biwa, and over 450 streams and rivers that run into her. And so, too, do the Omi cattle - but more of that a bit later.

First, I wanted to find out what makes Omi Beef so highly prized, and went to visit Takahisa Nagatani, a beef farmer and meat producer in Takashima, in the north of the prefecture, to learn more.

Nagatani owns Daikichi Beef, founded in 1896 by Daikichi Nagatani, and run as a family business for the 120 years since. Originally a meat shop and butchers, Nagatani now keeps a herd of five hundred Omi cattle, and no sooner had we arrived at his shop but we were back in the car to head up to the top of a nearby mountain to visit the yard.

My family run a small sheep farm in the UK, and it has always been drummed into me how important it is that animals are kept clean, peaceful and happy. Not only for their own welfare, of course, but also to produce the best tasting meat. Stressed animals release adrenaline, just like we do, which increases the acidity of the meat and makes it tough and sour. There are plenty of horrific images on the web of mass-farmed beef, thousands upon thousands of straggled cattle, squeezed into pens in mountains of their own dung and force-fed indigestible feed mixed with chemicals… Even a small cattle farm is generally a pretty pungent place, and although it’s not a smell I dislike so long as it’s fresh, I was prepared for a bit of a stink… But how wrong I was proved to be.

I think I have never seen a cow shed as pristine as Nagatani’s. There was hardly a spot of dirt in the yard or walkways, and the feeding troughs were immaculate, too. The heifers are kept inside, as is the way in Japan, but they had plenty of room in their pens, and apart from a slight smell of fresh dung, the regularly cleaned-out muck and open-walled barn letting plenty of air through meant there was hardly any smell at all. From the young ones just a few months old, up to the adults almost ready to go to slaughter, all the animals seemed peaceful and happy in their surroundings. A little nervous at first, as cows always are, they very soon became accustomed to us and were biting cheekily at my jacket as I talked with Nagatani. Beside the cow sheds, mountains of muck sit for a couple of years to compost, and it is then sold on to local rice farmers as a fabulously rich manure, helping make Shiga rice one of the top brands in Japan, too.

We were heading back to the shop to try some of the beef for ourselves, when Nagatani suddenly made a detour. “We’re running a bit late but I’ll just show you something,” he said, and we turned down a little lane running past the paddy fields, and stopped by the side of a wood where there was a standing stone with the inscription “Akiba no Mizu” - the Water of Akiba. Spring water that gushes from the mountains, and runs all the way down to feed into Lake Biwa. At a constant 12 degrees all year round the water is warming in the snowy months, and soothingly cool in summer - and tastes great all year round. This water, and other spring water like it that feeds into the lake, are the secret ingredient to all Shiga produce, and it is this very same spring water that is fed up to the barns for Nagatani’s cattle to drink. I tried a mouthful, from the cup left at the spring. Delicious, and one hundred percent natural - those are some lucky cows!

Back at Nagatani’s office, he explained how the meat is cut and prepared for sale. A Japanese butcher prepares cuts of meat in a different way to his western cousin, producing a range of precise cuts suitable for both Japanese and western cuisine. A few days before visiting Shiga I had taken an English friend on a rare trip to the famous Tsukiji Fish Market, and we had watched the fishmongers cut a tuna with their enormous sword-like knives, then fillet it into chunks, each wiped with a cloth to polish the surface and wrapped painstakingly, first in a layer of white, then green paper, all tied meticulously and elegantly with string, to be shipped off to the sushi chef who ordered it. The butcher’s workplace is given less of a spotlight in Japan than that of the fishmonger, but the care and precision of the two masters is easily on a par.

And then we got to try some Omi Beef for ourselves - and oh boy it’s good!

Nagatani’s staff had prepared three different cuts for us, grilled simply in salt and pepper and a little soy sauce. Each had its own unique flavor and texture, but two things struck me with all of them.

First, the delicate balance between the melt-in-your-mouth wagyu softness, and a satisfying bite for your jaws - a balance often lost in wagyu. And secondly, how clean and un-distracting the fat was. Wagyu is famous for its fatty marbling, of course, and it is the fat that gives the meat its unique flavor, but often the look of the raw marbled meat can take precedence over taste, and the flavor of the fat can get in the way. Not so with Nagatani’s beef - just pure,beefy goodness.

Our next stop after saying goodbye to Nagatani was Harie, where for hundreds of years the locals have used the natural flowing spring waters for their daily lives. Gin-clear streams run everywhere through the little town, and even now around 70 houses in Harie have pools inside their front door, or in a hut outside, where vegetables and rice are prepared, and dishes are washed with specially produced degradable detergent made from used cooking oil. Koi carp and Biwa trout swim wild in the streams, and live in the pools in each house, too. They are treated as members of the family, and not only do they keep the streams free of dirt and insects, but gobble up any left overs from cut vegetables or uneaten rice, too, keeping the pools crystal clear and sparkling. As we struggle to recycle our garbage and find ways to make our lives more friendly to the environment, it is sobering to see, in ultramodern Japan, the ultimate sustainable system that has been in place for hundreds of years and is still in use today, every day.

Next we headed further round the lake to visit L’Hotel du Lac - a discreet, exclusive boutique hotel, situated in probably one of the most idyllic settings anywhere in the world. As we sat talking with the manager, Hidekazu Tanaka, we watched the sun set over the lake, and the only man-made object in sight was a tiny lighthouse sparkling miles across the water. Then the chef brought us an exquisite plate of local Omi Beef in “jun-jun” sauce, with a wonderfully simple fresh tomato, snap pea and renkon garnish. Tanaka was explaining how the hotel and the local surroundings are dependent on each other, and as an example of that, the French-trained chef has created dishes that combine French cooking traditions with local sauces and ingredients. Jun-jun is a sweet, soy-based sauce famous in the area, and the arrangement with Omi Beef was just fabulous - a delicious, not-too-sweet, caramelly sauce so good that it made you want to dip your finger in and wipe the plate clean.

The sun had set and it was time to move on to our final Omi Beef of the day - dinner at Kyara, in Hikone. Located just at the entrance to Hikone Castle, at Kyara you can have Omi Beef prepared in almost any style you want, in your own private western or Japanese-style room. The steaks looked fantastic, but we opted for the local favorite, sukiyaki. After two light Omi Beef meals already that day, part of me was ready for something else, but once the sukiyaki arrived - gorgeous rose-pink meat, with plenty of vegetables, shiitake mushrooms and local red konyaku - my stomach started growling again. All expertly prepared at your table by your waitress, again the Omi Beef was terrific - the fat clean and fresh, and just enough bite to keep you chomping.

And so our day of Omi Beef came to an end. With over 400 years of history, and such a degree of care and delicateness in the breeding of the cows, the preparation of the meat and the cuisine itself, it is easy to understand how long ago the ancient shoguns of Japan found ways around the strict laws against eating meat, and had it prepared as “medicine” for their lordly tables. If wagyu is already one of the top brands of beef in the world, then no doubt about it, Omi Beef sets the standard.